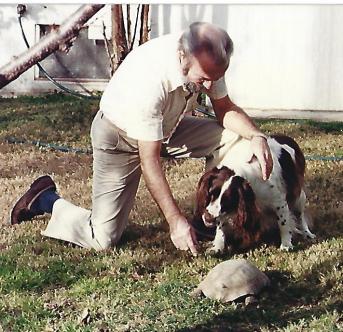

Our family built a backyard tortoise rescue operation in the 1950s and 60s.

My father worked at Edwards Air Force Base in California, site of the development and testing of the X15 experimental rocket plane, known widely as “the first airplane to reach Mach 3, Mach 4, Mach 5, and Mach 6.” As a small girl, I once watched close up (hands over my ears) as the plane broke the sound barrier.

My father’s drive to work took him from Ontario, on the desert edge of LA, along the San Bernardino freeway east until it veered north through a cleavage in the San Bernardino Mountains, into the desert toward Barstow, before finally swinging west toward Mohave. Long stretches of his drive were on roads dissecting the heart of the California high desert, where the tortoise has lived for over two hundred million years.

Man-made roadways like those he traveled slay thousands of desert tortoises.

Sometimes on his way to work or back my dad passed dozens of crushed tortoises. He once told of his fury at a truck driver he had seen deliberately target a tortoise and smash it.

Sighting the lumbering creature making its slow way across the highway, he had pulled over to the verge, intent on dashing into the road to save it when the way was clear. As he stood, visibly, at the road’s margin, a heavy truck veered into the direction of the tortoise, aimed directly at it, and crushed it under its heavy tonnage. My dad was livid.

Man, a planetary disease, its sickness spread by disregard for fellow planetary inhabitants.

On other occasions, spying a desert tortoise ambling across the highway, my dad would slow his Volkswagen bug to a near stop mid highway, scoop the tortoise up with his hand, and land it in the seat beside him.

It was for the protection of these creatures that we constructed “The Turtle Yard”—our tortoise rescue operation.

When my parents bought our home, they built a six-foot high brick fence enclosing the back yard. To create the turtle yard, my father added a wire fence covered in honeysuckle parallel to and about 20 feet from the yard’s west side wall. The back and west wall of brick, the inner wall of wire and honeysuckle, and a long, wood slat, red front gate enclosed a 20 by 80 foot section of bare dirt, to which my dad added a watering hole.

This yard housed our growing family of desert tortoises. We quickly collected 20 or 30. Rocky, a huge female, was the champion mama, laying the more eggs than all the others.

One morning, my mom looked out the kitchen window and began yelling. “Ted, Rocky’s loose.” Then, moments later, “Why, it must be Traveler too.” Then louder, and in a more agitated voice, “Ted, come here. The turtles got out! We’ve got turtles all over the back yard!”

They weren’t our tortoises though.

One of my father’s friends had been to a “turtle race.” When no one knew what to do with the assembled tortoises, he offered to transport them to our house and dump them over the back fence. Our tortoise menagerie grew that day from 40 (we were hatching babies) to over 80.

I must have been the only child in my elementary school with a mega tortoise collection. One day, my elementary school principle called me to his office to determine if a large tortoise found wandering on the school grounds was mine. I looked it over. “No, I don’t think so,” I said, “but I’ll take it home anyway.” So that afternoon, I lugged the monster two blocks home to join our tortoise family, where it was welcomed. We did not know, though, that the new tortoise carried a bacteria (either Mycoplasma agassizii or Mycoplasma testudineum), an upper respiratory disease sweeping through the California desert tortoise community.

Soon, a number of our tortoises died from the ravages of this emerging illness.

When this disease struck, we were devastated. Although we had sought to help save the species from human encroachments into their environment, we could not save them from the puzzling illness decimating our tortoise family and so many more of their feral siblings.

This disease was another blow in a list—crushing by automobiles and off-road vehicles, urban development taking over their habitat—that confronted this ancient species. Today, even climate change, causing drought conditions, threatens their survival.

The California desert tortoise has decreased by 90% since the days my father sought to save them in the 1950s and 60s. His way of doing so—scooping them up and bringing them home—is illegal today.

Instead, reserve habitats—one of which became the home of our remaining tortoise family after my father died—are dedicated to their survival. To help save the species, people can even legally “adopt” a tortoise through the California Turtle and Tortoise Club.

During my childhood, our rescue plan seemed like a good strategy, but it was insufficient. Yet like the hardy Bristlecone pine, the California desert tortoise still survives—barely—amidst its alarming losses and reduced habitat. Other species, less supported by preservation efforts, may not persist at all, though, unless more people stop acting like planetary diseases and begin behaving like co-inhabitants of a shared globe.

We need to stand up for this planet. People of all religious, political, cultural, national, and other differences need to take a stand against greed and for the earth.

We have a common stake in this.

I struggle to be effective as an environmentalist. But I know this: more people must work together than are currently doing so if we are to protect this planet, home to over 7.6 billion humans and a host of other incredibly wonderful species.

Our garage—my dad’s domain—was a black widow spider haven with its dingy, dust-filled corners, crammed spaces, and caved in boxes, piled awkwardly one inside another, empty, like promises unfulfilled.

Our garage—my dad’s domain—was a black widow spider haven with its dingy, dust-filled corners, crammed spaces, and caved in boxes, piled awkwardly one inside another, empty, like promises unfulfilled.

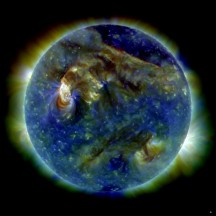

Harsh, yes. But true also. The disease is dangerously out of control. Still, we can fight it. We weren’t meant to be a plague on this beautiful blue and green planet.

Harsh, yes. But true also. The disease is dangerously out of control. Still, we can fight it. We weren’t meant to be a plague on this beautiful blue and green planet.