I’ve had some terrible experiences with pets. When one of my pet white rat mothers died, leaving the remaining mother with 13 babies, and this mother went insane, suffocating and partially eating the babies, I learned of the horrors that can occur in nature.

When I discovered our beloved cat Midnight stiff in the ivy beside our garage–she, along with several other animals in our neighborhood, had been poisoned overnight by an unknown, vicious person—I wept.

When a tortoise found wandering around my elementary school was given to me by the school principal and I took it—a little girl carting it for blocks to offer it a home alongside our own desert tortoises—but then we discovered that this tortoise carried an upper respiratory disease sweeping through the California desert tortoise community that soon killed a number of our family’s tortoises, we all grieved.

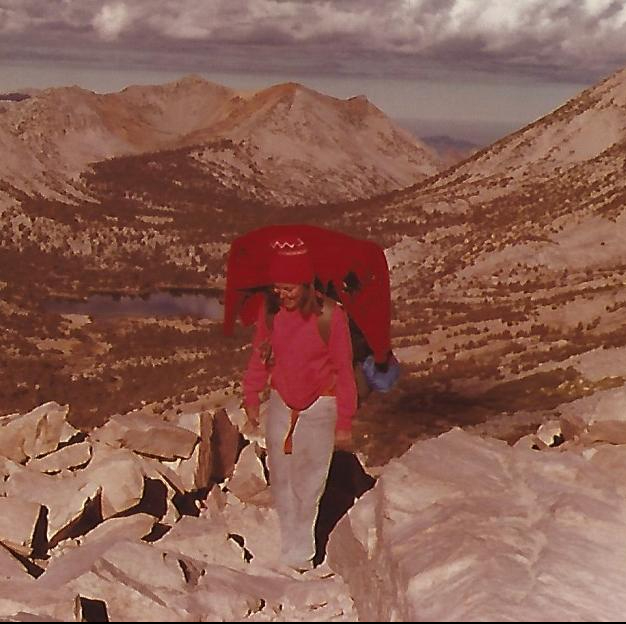

Loving other animals (humans are animals too) has confronted me with horror, tragedy, mourning, and loss. Yet my life has been replete with animals. This picture of me is evocative: encircled by turtles, holding a cat, with a puppy nearby! Paradoxically, it was in caring for such animals that my love for nature was nurtured.

Loving other animals (humans are animals too) has confronted me with horror, tragedy, mourning, and loss. Yet my life has been replete with animals. This picture of me is evocative: encircled by turtles, holding a cat, with a puppy nearby! Paradoxically, it was in caring for such animals that my love for nature was nurtured.

When I was growing up, our family rescued, hatched, and raised over 80 desert tortoise—keeping most in our improvised “turtle yard.”

My mom couldn’t say no to any dog who, frightened by the sound of fireworks, found its way to our front porch year after year on the 4th of July. We always tried to find a lost animal’s home before keeping it, but quite often the lost pet became ours.

Before her murder, our cat Midnight gave birth to a litter of kittens and Shadow (the one we kept) lived to be 21 years old—a full life.

We brought home tadpoles, hatched them, and then loosed them in the thick ivy of our back yard. For over a decade, huge toads, bloated by a diet of flies, mosquitoes, and grasshoppers, emerged from the ivy, living high on the prolific insect supply.

When one of our cats caught birds, and brought them to our porch to show off its prize, when possible, we rescued, tended, and released them.

Our family cared for dogs, cats, tortoises, white rats, a skunk, a chipmunk, birds, frogs, horny toads, and fish. Many lived into old age, the tortoises saved from roads littered with roadkill, dogs taken in and made part of the family, and cats living to die natural deaths in a secure home.

Sometimes the tragedies seemed to exceed the joys, as they sometimes do in the rest of life. But most of life is composed of everyday experiences, and my daily life intermingled with that of these animals. I learned that caring for the animal world is work, dangerous, messy, and sometimes terribly sad; and it is full of love, joy, and the opportunity to observe, tend, and appreciate our fellow earthly inhabitants.

Tending and loving them is personal, practical, local, national, global, and must reach the level of policy.

Humans were not given the earth for ourselves (if you believe in the record in Genesis). We were meant to be caretakers, not takers.

Humans are big, and powerful, and violent, and our interactions with the world have often been deeply destructive. We have functioned as a “planetary disease,” destroying the environment on which all species depend. Yet our human world is only one of a myriad of other worlds God made that coexist with ours but are often out of sight, worlds inhabited by birds, fish, reptiles, insects, and mammals like ourselves.

Today, five bird feeders surround my home, and I watch these winged creatures in a fairly natural habitat. This spring and early summer, pine siskin, red robins, American goldfinch, red cardinals, house finch, woodpeckers, nut hatch, and humming birds have roamed my gardens. The birds tend to their own needs; my feeders merely add to their pleasure.

I am less acquainted with the birds’ sorrows than I have been with those of my pets. But I’m aware that suffering takes place. Out of my sight, tragedies are unfolding. I’ve been acquainted with great loss associated with loving creatures from these other worlds. I’ve felt horror at their suffering. So today, when I hear of sea turtles, seals, seabirds, fish, whales, or dolphins suffering and dying after ingesting plastic, I grieve. When I hear of disappearing species, lost due to habitat destruction, I mourn.

Perhaps the sorrow I’ve known as a pet owner has developed compassion for these earthly fellow-inhabitants, stirring my concern for the natural world. I hope so. And I’m trying to turn my sorrow infused concern into more responsible actions.

In every election—local, state, and national—you have the opportunity to do the same. In your workplaces and your homes, you can seek to care for the world rather than injure it. Listed below are a few key organizations that can help—most have local chapters where you can become engaged. We must all find ways to turn a love of nature into urgent action.

Oranges and lemons, from California, to Texas, to Florida, to the U.S. Virgin Islands, are at risk today from a plant disease known commonly as Citrus Greening (short for Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus—a name I’ll never remember). Apparently it is one of the most serious plant diseases in the world. The

Oranges and lemons, from California, to Texas, to Florida, to the U.S. Virgin Islands, are at risk today from a plant disease known commonly as Citrus Greening (short for Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus—a name I’ll never remember). Apparently it is one of the most serious plant diseases in the world. The

At the Rose Parade, flowers reign. For those unversed in parade rules–every surface inch on every float—from huge twirling elephants to the image on the elephant’s IPad—must be covered in natural materials–dried stretched seaweeds, tea leaves, cranberry seeds, corn, beans, or rice. Herbs like cumin and cloves. Carnations, mums, daisies, orchids, bird of paradise flowers, and half a million or more roses. No artificial plant materials or coloring are allowed—nature’s colors are dramatic enough.

At the Rose Parade, flowers reign. For those unversed in parade rules–every surface inch on every float—from huge twirling elephants to the image on the elephant’s IPad—must be covered in natural materials–dried stretched seaweeds, tea leaves, cranberry seeds, corn, beans, or rice. Herbs like cumin and cloves. Carnations, mums, daisies, orchids, bird of paradise flowers, and half a million or more roses. No artificial plant materials or coloring are allowed—nature’s colors are dramatic enough.

“I’m conducting tests. I want to know how long it takes to polish these raw stones.”

“I’m conducting tests. I want to know how long it takes to polish these raw stones.”

The fish we hunted often hid beneath fallen logs. They lay concealed, watching for a fly or mosquito to land and float up close. The partially submerged trees gave the fish the chance to surprise a bug and snag its dinner.

The fish we hunted often hid beneath fallen logs. They lay concealed, watching for a fly or mosquito to land and float up close. The partially submerged trees gave the fish the chance to surprise a bug and snag its dinner.

s extinguishing marine species. Plastics are choking the ocean with plastic islands. “So much plastic is ending up in the ocean that in just a few years, we might end up with a pound of plastic for every three pounds of fish in the sea,” warns the

s extinguishing marine species. Plastics are choking the ocean with plastic islands. “So much plastic is ending up in the ocean that in just a few years, we might end up with a pound of plastic for every three pounds of fish in the sea,” warns the

But is it? Eiseley’s star thrower had a more hopeful view than his beach walker.

But is it? Eiseley’s star thrower had a more hopeful view than his beach walker.