Hiking by ourselves in the California High Sierras, my husband John and I camped far above timberline, beside a still, pristine lake, surrounded by heavy boulders in lieu of mountain pine. That evening we ate big golden trout, unwary and easily caught, for our dinner.

As my father and I had done when I was a child, John and I slept tent free, open to the night around us. Rain came infrequently in September in the Sierras. We preferred to sleep only in downy sleeping bags, our vision unfettered by a covering of canvas. In this place, far above civilization, out of reach of star-dimming light, on a moonless, clear night, the sky seemed embodied with stars and galaxies.

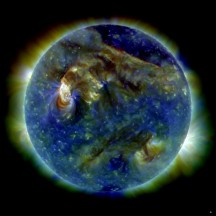

Knowing better, I extended my arm, wanting to touch them, caress them. Thousands of stars—some shining pure light, others shimmering—painted the black sky with gleaming dots of white.

We were on the edge of the world, high above the level places, where the atmosphere thinned and the night was black and the stars were the prime attraction.

Glorious stars like those we saw that night bear witness to their Creator. I had learned this on an earlier star sighting. On a dry, clear night, perfect for looking at a brilliantly lit, star-studded sky, as my father and I stopped our car on the verge of Interstate 10 and stepped through a row of eucalyptus trees to view the sky, I first encountered the stars capacity to inspire awe.

As I described in another post, that night glowing stars peppered the heavens to the borders of my vision. The Milky Way blazed in transcendent glory. As I looked at that brilliantly lit night sky I sensed a living presence, bigger than myself, or my father, or even the expanse of stars that filled the sky. It was a pressing presence, a voice of a different kind, so clear that I have never forgotten it. I never want to.

We often looked for stars when I was a child. Through a telescope, set up on our asphalt driveway, we picked out one constellations after the other. Camping high on Mount Baldy in the San Bernardino Mountains, we watched stars traverse the sky with our naked eyes.

These experiences tell me that stars are more than the sum of the luminous gasses of which they are composed. They are more than beautiful glowing dots in the sky. They have a voice of their own and they cry out in praise of their Creator.

“The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands” (Psalm 19:1).

Scientists say that at least a third of all the people in the world cannot see the stars at night now, because of light pollution. Many more people—as many as two thirds of all who live in the United States–see only a few stars, indistinctly.

Most of us forget even to look up. We have successfully blinded ourselves to the grandeur of the night sky that boundlessly bears witness to its Creator.

Light pollution hurts other creatures as well as ourselves. Bright city lights can confuse migrating birds, causing them to fly over cities until they die of exhaustion. Light from developments on beaches and nearby cities can scare sea turtles off from nesting.

We can do something about light pollution, if we make it a priority. Bending lights downward, rather than upward on city roads would be a start. It would cost us something. But I believe removing light pollution, like other environmental measures, will be worth the cost.

Instead of maximizing profit, those placed here to tend the earth should be minimizing the harmful impact we have on the planet, ridding ourselves of human pride, and letting the earth serve the needs of all its inhabitants, plants and animals. The land, water, air, and even the atmosphere above us are all affected by human activity. We have far to go to tend this planet as we should. I want those stars to speak as loudly to future generations as they have done to me through star sightings

By doing so, we may remove an impediment that we have created between ourselves and the voices of incalculable galaxies declaring the glory of God.

Full photo credit: Wikimedia. Taken 10 February, 2010. ESO/J. Emerson/Vista http://www.eso.org/public/images/eso1006a/

Our garage—my dad’s domain—was a black widow spider haven with its dingy, dust-filled corners, crammed spaces, and caved in boxes, piled awkwardly one inside another, empty, like promises unfulfilled.

Our garage—my dad’s domain—was a black widow spider haven with its dingy, dust-filled corners, crammed spaces, and caved in boxes, piled awkwardly one inside another, empty, like promises unfulfilled.

Harsh, yes. But true also. The disease is dangerously out of control. Still, we can fight it. We weren’t meant to be a plague on this beautiful blue and green planet.

Harsh, yes. But true also. The disease is dangerously out of control. Still, we can fight it. We weren’t meant to be a plague on this beautiful blue and green planet.