Our garage—my dad’s domain—was a black widow spider haven with its dingy, dust-filled corners, crammed spaces, and caved in boxes, piled awkwardly one inside another, empty, like promises unfulfilled.

Our garage—my dad’s domain—was a black widow spider haven with its dingy, dust-filled corners, crammed spaces, and caved in boxes, piled awkwardly one inside another, empty, like promises unfulfilled.

This space was an odd reflection of both my father’s strengths and his disappointments.

His big workbench filled one end of the square garage, while a long chest of drawers heavy with nails, screws, bolts, old metal bits, wires, tools, sandpaper–the odd assemblage of a WWII aeronautic mechanic—filled another: treasured opportunity to my dad, the son of a ranch hand and farmer, an airplane mechanic by profession, and a scientific inventor at heart; and interesting to me, a scruffy child in need of new discoveries.

As messy as it was, my dad’s garage fostered learning. It was there he constructed a rock polishing machine where I discovered that hidden beauty glistened in ordinary chunks of the earth’s crust.

My dad constructed a vice for me there on a small workbench, and I learned to use a hammer and saw. We built a wooden airplane; I sanded a wood block into a cross; we constructed a go-cart.

It was there he built an incubator where we hatched desert tortoise eggs. (Later, we learned that they did better nestled in a box under our water heater.)

As I wandered through the garage one day, my dad handed me a booklet. “Here, you should read this,” he said in his gruff-hiding-love type voice.

I took the booklet and read the title: “Man, a Planetary Disease.” Wow. Not a comforting title to an emerging young adult. I was still trying to figure out who I was, whether I had anything to offer the world, whether I was likable, how to clear up my pimples. I looked the booklet over, imprinting its title in my brain, but at the time, I did not read it.

I have read it since, though, and I have come to believe that my dad and the booklet’s author, Ian L. McHarg, understood something important.

In the B. Y. Morrison Memorial Lecture in 1971, McHarg argued:

Man is an epidemic, multiplying at a super-exponential rate, destroying the environment upon which he depends, and threatening his own extinction.

He treats the world as a storehouse existing for his delectation; he plunders, rapes, poisons, and kills this living system, the biosphere, in ignorance of its workings and its fundamental value.

The real battle in the world is not between communists and capitalists, black and white, rich and poor, green and purple, heliotrope or gamboge. The real fundamental division in the world is between the people who are not planetary diseases and those who are ….

You may find those words a bit harsh. Obviously, I found it off-putting when I first read McHarg’s title. But McHarg spoke at a time when the world was threatened by nuclear war, DDT, and chemical pollutants inexcusably spewed by irresponsible corporations.

Today’s environmentalists speak amidst other troubles: the threat of nuclear war, biological war, chemical war, everyday war, household pollutants, agricultural pollutants, corporate pollutants, habitat degradation, a killer wildlife trade, plastic islands in our oceans, climate change, and people eager to plunder and rape the world for short-term profit.

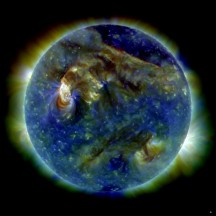

Harsh, yes. But true also. The disease is dangerously out of control. Still, we can fight it. We weren’t meant to be a plague on this beautiful blue and green planet.

Harsh, yes. But true also. The disease is dangerously out of control. Still, we can fight it. We weren’t meant to be a plague on this beautiful blue and green planet.

My dad was an environmentalist before the word became popular. He passed his love of the earth, seas, land, rocks, and trees on to me. Later, God stamped this concern deep in my soul. People were not made to conquer the earth; we are to care for it as beings who are interdependent with its other creatures and with its complex systems.

We must stop our greedy practices, restore and extend systems designed to let the whole earth flourish, and cherish this beautiful planet. We can do this, but it will take personal and political will if we are to do so.

If we do not, and if we do not see the need to do so as urgent, then we will destroy the planet we call home—we truly will be a planetary disease of epidemic proportions.

e had been trekking through Death Valley and Saline Valley, two basins east of the Sierras and south and east of the White Mountains. We were traveling in my father’s wildly outfitted Land Rover. The Rover looked like an ancient space vehicle—painted grey with patches of bright red, a pop-up tent carved out of the roof, and removable shelves that flung out like wings from its windows and doors.

e had been trekking through Death Valley and Saline Valley, two basins east of the Sierras and south and east of the White Mountains. We were traveling in my father’s wildly outfitted Land Rover. The Rover looked like an ancient space vehicle—painted grey with patches of bright red, a pop-up tent carved out of the roof, and removable shelves that flung out like wings from its windows and doors.